Governments are obliged to protect the human rights of all people within their jurisdiction. The most severe forms of “hate speech” that constitute incitement to hostility, discrimination or violence, as well as incitement to genocide or other crimes against humanity, must be prohibited by law.

When can the right to free expression be restricted?

Because freedom of expression is so important, the State must justify any limits it places on it, including limits on “hate speech”. International human rights law doesn’t just draw a line around what can and cannot be said, but sets out strict criteria to which States must adhere to justify any restrictions on free speech. These criteria form a three-part test to assess whether the restriction is 1) legal, 2) pursues a legitimate aim and 3) is necessary and proportionate.

The Three-Part Test

-

Legality

Restrictions must be clearly set out in an accessible law. This ensures that people are able to understand the laws so they can regulate their behaviour.

It also means that laws are unambiguous in the powers that they give to public officials to limit expression. With this clarity, laws give public officials less discretion, meaning they are less able to abuse their position to act arbitrarily against expression simply because they don’t like it or disagree with it.

-

Legitimate aim

Restrictions must pursue one of a few narrowly defined objectives set out in international law. This includes protecting the rights of others, for example the right to life, or for protecting public order or national security.

It is not a legitimate aim to limit expression simply because it is offensive, because it is critical of a religion or belief, or because it questions people in positions of power.

-

Necessary and proportionate

Restrictions must be necessary. In the case of limitations on “hate speech”, this means a government must be able to demonstrate a real threat is posed to a person or group’s enjoyment of rights on terms of equality, and that this limitation on the expression is the least restrictive way to prevent that harm.

Restrictions must also be proportionate; to block an entire website in response to a single article or image on that website constituting “hate speech” would not be proportionate.

Restrictions that do not comply with the “three-part test” violate the right to freedom of expression.

Severity of harm

Categorising “hate speech” according to its severity

International human rights law is clear that while all “hate speech” raises concerns in terms of intolerance and discrimination, not all “hate speech” should be prohibited through the law. At the same time, international human rights law singles out the most severe types of “hate speech”, defining the exceptional circumstances in which “hate speech” is so dangerous that States are required to prohibit it.

Understanding where to draw the line between “hate speech” that is simply offensive and objectionable, and “hate speech” that requires the State to respond through legal measures (e.g. to prosecute or fine an individual) is important.

The pyramid below categorises “hate speech” into four levels according to its severity, to help identify what responses will be appropriate under international human rights law.

MUST BE RESTRICTED (Genocide Convention / Rome Statute)

This level shows us hate speech that must be prohibited. International criminal law requires States to prohibit incitement to genocide. Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, defines “genocide” as the commission of one of five specified acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part”, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”. Article 3(c) prohibits “public and direct incitement to Genocide”.

exampleMUST BE RESTRICTED (Article 20 (2) ICCPR)

This category includes “hate speech” that is so severe that it must be prohibited. Article 20(2) of the ICCPR requires States to prohibit the advocacy of discriminatory hatred constituting incitement to hostility, discrimination or violence.

exampleMAY BE RESTRICTED (Article 19 (3) ICCPR)

This level shows us “hate speech” that may not constitute “incitement”, but which may nevertheless pose serious dangers of harm. “Hate speech” in this category might include direct threats of violence against an individual or group because of who they are (i.e. the speaker does not incite others to commit violence, but threatens to commit violence him or herself).

Under Article 19(3) of the ICCPR, the Government can limit expression to “protect the rights of others”, and for “public order”, provided that these restrictions meet the “three-part test”.

exampleMUST BE PROTECTED (Article 19 ICCPR)

Lawful “hate speech”. This may include speech that is discriminatory, including expression that is offensive and objectionable, but does not directly threaten harm against individuals or advocate discriminatory hatred that incites others to cause harm against individuals.

This type of expression is protected under Article 19(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. However, the discriminatory attitudes that such expression evidences raises concern in terms of intolerance, and still requires a response from the State. However, that response must be made through other measures, such as education or policies for public officials to speak out against hatred, rather than through laws that punish the expression itself.

exampleExamples

The leader of a prominent armed group, with territorial control over part of a country, frequently addresses the public through online videos. The armed group believes in their superiority on the basis of their religion, and expressly seeks to establish a theocracy. As the rule of law has diminished in the territory and public services have become non-functioning, the leader has sought to blame these problems on a religious minority group through a series of online video posts. The narrative implies the minority group is engaged in sabotage, and planning a violent revolt. As unrest in the territory increases, a new video calls on “the faithful” to act immediately to ensure a “pure” future for the fledging State. He calls for the streets “to be cleaned” with the blood of the religious minority, in particular the men, and tells followers that the destiny of minority women is to be enslaved for sexual exploitation, so that their offspring can be brought into the majority religion.

This scenario describes in quite clear terms an incitement to an act of Genocide, prohibited under the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute (referred to as international criminal law). Beyond the requirements of Article 20(2) of the ICCPR, incitement to Genocide requires proof that there was specific intent for Genocide to occur as a result of the incitement. Intent is determinative in these cases, as it must be proven that the speaker intended their incitement to lead to the destruction, in whole or in part, of a racial, national, or religious group. The speaker’s leadership position and level of influence, as well as his narrative of religious purity, combined with the content of the most recent of his video clips, shows clear genocidal intent towards the religious minority in his territory.

Examples

In the run-up to a heavily contested presidential election, the incumbent president makes a series of speeches to large rallies. During these rallies, he promotes a rumour that supporters of the opposition, mostly belonging to another ethnic group, are arming themselves and pose a threat to his supporters. As tensions increase, he uses racialised language, reminiscent of calls used to incite mass-killings in the country a few decades earlier, calling on his supporters to take urgent action to secure an election victory, saying “the time has come”.

Here, the President has engaged in “hate speech” which arguably reaches the threshold of advocacy of hatred that constitutes incitement to violence. He understands and is exploiting ethnic tensions in society and is aware of the history of conflict between the ethnic groups in the past. He knows that as an influential politician, his use of these particular terms at an emotionally charges time would be understood by the audience as a direct call to violence. He knows the audience would likely act on his words to go and commit violence against, and even kill, members of the ethnic group associated with the opposition party. Whether or not violence actually ensues, criminal sanctions for this type of expression would be justifiable.

Examples

A refugee family boards a busy bus, occupying several seats. Another passenger, unable to sit, complains loudly, blaming refugees for draining public resources. She then verbally assaults the father using racist language to insult the family, who all fear for their safety during this attack.

In many countries, laws on public order prohibit behaviour that intentionally intimidates others, especially where it causes fear of assault. Often laws will recognise a more serious offence where the perpetrator is motivated by bias (e.g. racism). Sometimes, “hate speech” laws may also prohibit this type of intimidating behaviour.

While making offensive comments on public transport may not justify a criminal law intervention, when individuals are made to feel threatened and fear for their immediate safety, restrictions may be justified under Article 19(3) of the ICCPR. But any sanctions must be proportionate. Depending on the severity of the situation, a formal warning from the police, an order to pay compensation to the victims, or perform community service may be more appropriate than a prison sentence. There are also measures governments can take to prevent these harms, for example through campaigns against “hate speech” and intimidating behaviour on public transport.

It is important to distinguish this behaviour from advocacy of hatred that constitutes “incitement”, which must be restricted. While some cases of verbal threats and assault may be as severe as incitement, the relevant contextual factors to consider are different. In the case of the refugee family, the speaker’s level of influence over her audience (other passengers on the bus) is not of concern, nor is the likelihood that other passengers will engage in violence against refugees as a consequence of what she has said.

Examples

Following a bombing of a Sufi Mosque, a teenager in a city several hundred miles away updated his Facebook status to say the victims “deserved it” for choosing to be followers of the Sufi tradition. The teenager has several hundred “friends”, and the post prompts heated responses on both sides; the user is not a politician or a public leader.

In several countries overbroad “hate speech” or counter-terrorism legislation could be wrongly used to prosecute this teenager, even though the expression neither intends nor is likely to incite another terrorist attack. Though deeply offensive and “hate speech”, it is unlikely given its context to meet the threshold of “incitement”, where the Government would be required to impose restrictions. Though Facebook may decide to remove the comment under their terms and conditions, they should not be obliged by law to do so.

Assessing restrictions on incitement to violence

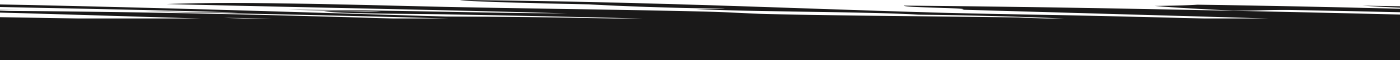

Incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence is a specific form of “hate speech” that involves three actors:

- the “hate speaker”;

- the public audience, who may engage in acts of discrimination hostility or violence;

- and the target group, who may be the victims of these acts.

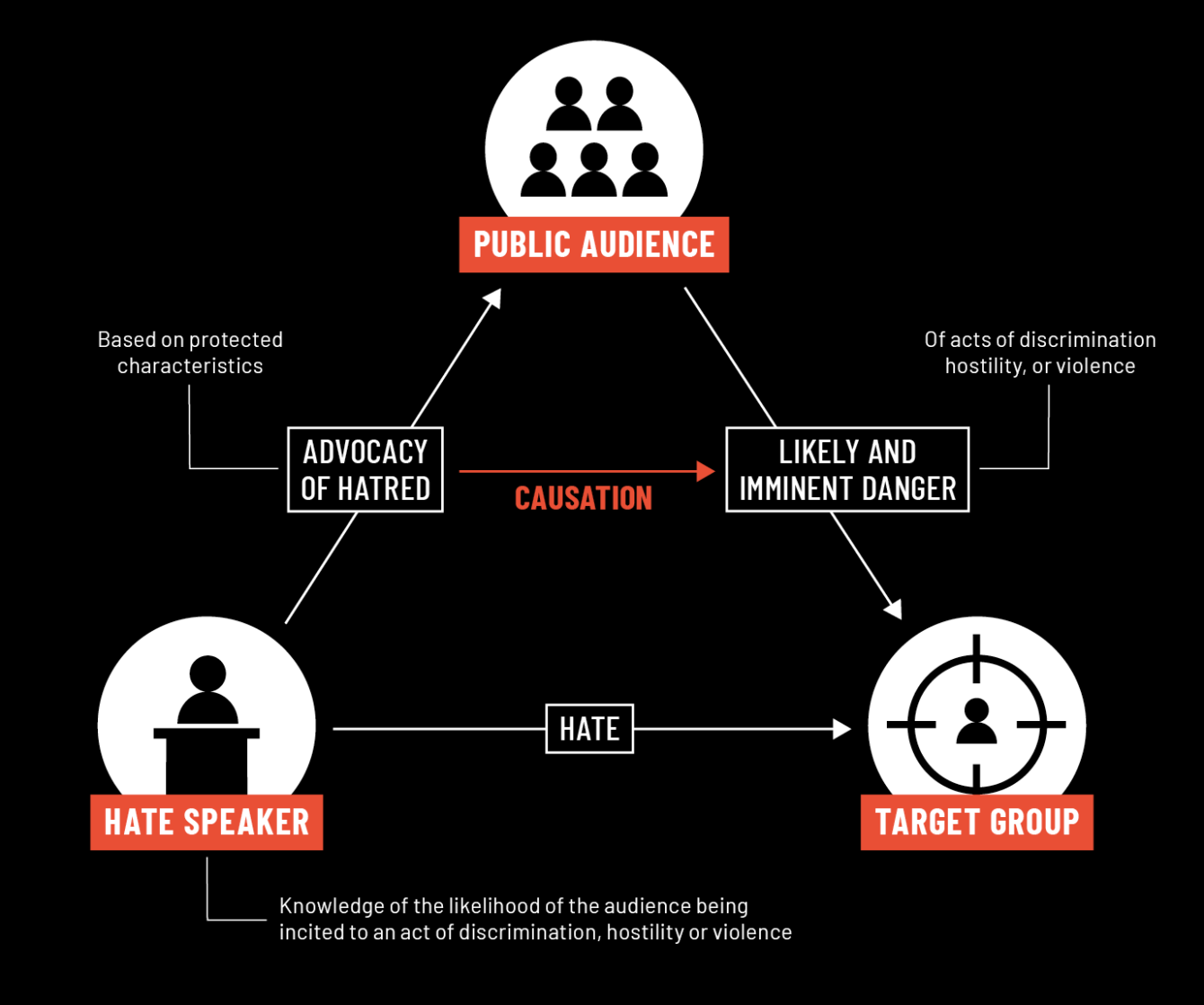

Six-part test

In order to know when incitement to discrimination or violence is severe enough to restrict, a six-part legal test can be applied.

Restrictions on hate speech quiz

Question 1 |

Why must government restrictions on hate speech always be narrow and clearly defined?

This is to ensure that lawful criticism or dissent are not mislabelled as hate speech. Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

People must be able to understand the laws so they can regulate their behaviour Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

Overly broad restrictions can overlook people's ability to tackle prejudice and discrimination with counter speech Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

All of the above |

Question 2 |

Article 19's 3 part test helps ensure that restrictions on hate speech are narrow and clearly defined. What criteria does the 3 part test require?

All restrictions should be precisely worded and provided for by law Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

They should be in pursuit of a legitimate aim, such as protecting the rights of others Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

They must be necessary in a democratic society; this means that the government should be able to demonstrate that there is an actual threat and that a restriction is both necessary and proportional. Hint: That's partially right. What else? | |

All of the above. |

Question 3 |

Why must restrictions on hate speech be made using a cautious and context-specific approach? Check all that apply.

Prohibitions are often too broad and may be enforced to shield those in power from legitimate criticism. Hint: That's partially right. There are other reasons. What else? | |

Broad prohibitions are more likely to marginalise minority voices. Hint: That's partially right. There are other reasons. What else? | |

It is easy to mistakenly assume that speakers mean to harm when they may mean to provoke thought or debate. Hint: That's partially right. There are other reasons. What else? | |

It is easy to misjudge the influence of a speaker. Hint: That's partially right. There are other reasons. What else? | |

Too much control limits our right to seek, receive and impart information. Hint: That's partially right. There are other reasons. What else? | |

All of the above |

Question 4 |

Why are civil rather than criminal sanctions better at challenging hate speech? Check all that apply.

Civil or administrative sanctions focus on meeting the victim's needs while criminal sanctions focus on punishing offenders. | |

They are not. Punishing offenders through criminal sanctions is an excellent way to deter people from using hate speech. | |

Civil measures include compensation for the victims, public apologies, imposing fines and giving victims the right of correction and reply. | |

Criminal sanctions do not allow us to tackle the root causes of hate speech. If we want more equal and just society we need to tackle discrimination and intolerance with more than a prison sentence. |

Question 4 Explanation:

Recourse to criminal law should be avoided if less severe sanctions would achieve the intended effect. Criminal penalties should be imposed as a last resort, and only in the most severe cases.

There are 4 questions to complete.

|

List |