What is hate speech?

Put simply, “hate speech” is any expression of discriminatory hate towards people based on a particular aspect of their identity.

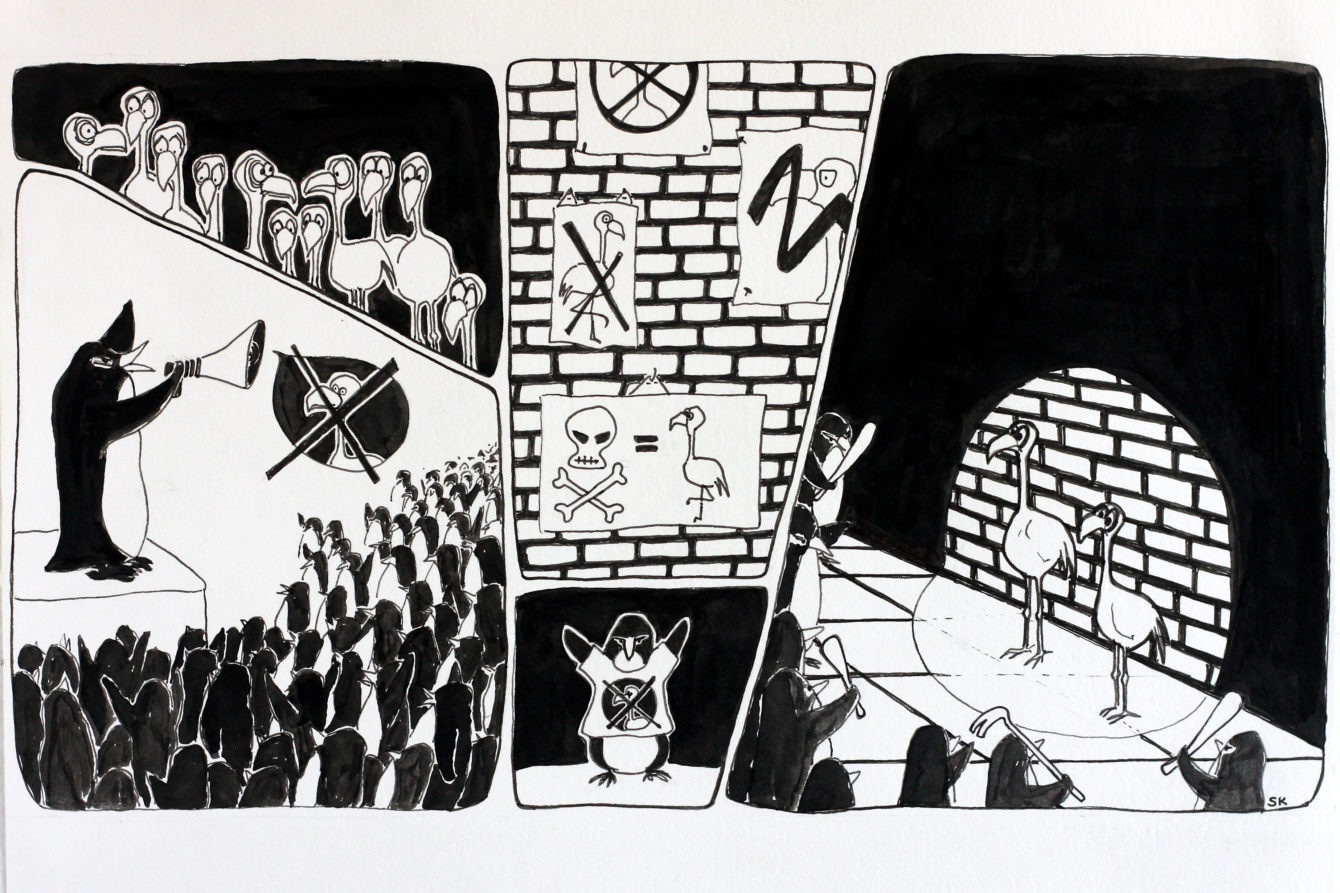

“Hate speech” can be especially dangerous when it seeks to incite people to violence against marginalised groups. But even less severe forms of “hate speech”, such as repeated insults and slurs or harmful stereotypes can create toxic environments and have consequences. “Hate speech” can lead people to feel their dignity is constantly under attack, potentially causing psychological harm as well as contributing to broader forms of social, political, economic and cultural marginalisation.

It is important that we recognise that all “hate speech” is harmful, and that ensuring the human rights of all people are protected requires challenging hate in all its forms.

But what’s ‘hate speech’?

There is no universally agreed legal definition of “hate speech”.

“Hate speech” is a very broad term – and can be used to describe any discriminatory expression that denies the humanity of others or incites harm. Such speech undeniably has a negative impact on societies, in particular for minority and marginalised groups.

International human rights law is clear that expression cannot be limited solely on the basis that it is offensive or insulting, and this includes speech that may be hateful and discriminatory. However, governments are required to limit expression where it is so clearly dangerous that limitations are the only way to prevent serious harms. These types of expression may be understood as the most severe forms of “hate speech”, namely the advocacy of discriminatory hatred which is intended and likely to incite violence, hostility, or discrimination. Restricting direct threats of discriminatory violence, for example, may also be restricted.

Generally speaking, national governments define these terms in their own laws, which is why approaches vary so greatly between countries. Confusion has led to many laws being enacted that do not comply with international human rights law.

But around the world we see problems with “hate speech” laws defined by governments. On the one hand, powerful individuals incite or threaten violence with impunity where they should be held accountable. On the other hand, laws are abused to target legitimate dissent in many parts of the world when such speech should be protected.

Who is the target of hate speech?

Anyone can be the target of “hate speech” just for being different.

However, it’s important to understand that criticism of a person because of their behaviour or their ideas is not necessarily “hate speech”.

International human rights law recognises a range of different characteristics that people should be protected from discrimination on the basis of. This includes but is not limited to their:

- Race

- Sex

- Colour

- Religion

- Nationality

- Gender identity

- Sexual orientation

- Disability

- Migrant or refugee status

- Indigenous origin

For example, expressing hatred towards a politician because you disagree with their ideas or policies is not necessarily “hate speech”. But if you express hatred against a politician because they are a woman, or because of the colour of their skin, then that is “hate speech”.

‘Hate speech’ targets people because of who they are.

ARTICLE 19 considers that grounds for protection against ‘hate speech’ should include all those protected characteristics which appear under the broader non-discrimination provisions of international human rights law. While this may seem obvious, it is sometimes contested.

A patchwork of overlapping international and regional instruments has resulted in divergent approaches to different forms of ‘hate speech’ in domestic law, including in relation to the protected characteristics.

ARTICLE 19 argues that the realisation of human rights should not be constrained by an overly formalistic commitment to the original wording of any international legal instrument, or even to the intent of the drafters, if that interpretation would unnecessarily narrow the enjoyment of rights.

Also, international human rights instruments have been interpreted over time to support the principle of equality on a broad understanding of the term, applying to protected characteristics specifically listed in treaties as well as to grounds not expressly listed. Many States recognise protected characteristics in national laws prohibiting ‘hate speech’, which are reflective of the characteristics protected under their broader obligations to guarantee equality and non-discrimination.

With sufficient safeguards for freedom of expression, we consider that ensuring ‘hate speech’ provisions should be inclusive of the broadest range of protected characteristics. These should include but not be limited to: race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, indigenous origin or identity, disability, migrant or refugee status, sexual orientation, gender identity or intersex status.

Is all “hate speech” the same?

“Hate speech” can range from ignorant discriminatory comments and offensive jokes to explicit calls for discrimination against a group, or at worst, calling for mass murder.

International human rights law singles out specific categories of severe “hate speech” that governments must prohibit. This includes speech that actively promotes discriminatory hatred in such a way that it incites the audience to take action to harm the targeted group, simply because of who they are. That harmful action might be violence, discrimination, or another hostile act.

If some “hate speech” is merely insulting or offensive, and other “hate speech” incites people to murder, it is important that we can accurately identify what kind of “hate speech” we are dealing with in any particular scenario.

In order to identify appropriate and effective responses to hate speech, we need to understand the root causes of hate first.